Stasis: Presidential Electoral Maps Are in a Historic Holding Pattern

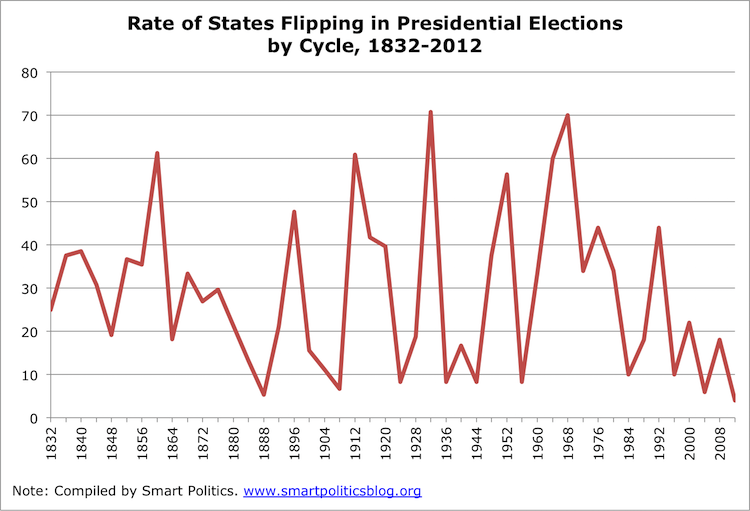

Not only did the 2012 map record the lowest ever rate of states flipping from the previous cycle, but the country is also currently in the midst of its lowest rate of change across the last three-, four-, five-, six-, seven-, eight-, and nine-cycle periods

From cycle-to-cycle, it is a virtual certainty that the partisan breakdown of the electoral map for president will change at least a little bit from previous election, as it has happened in every presidential race since the introduction of the two-party system more than 185 years ago.

From cycle-to-cycle, it is a virtual certainty that the partisan breakdown of the electoral map for president will change at least a little bit from previous election, as it has happened in every presidential race since the introduction of the two-party system more than 185 years ago.

However, in recent years, the list of ‘battleground’ states seems to be getting smaller with fewer states truly up for grabs.

Even still, as a recent Smart Politics report documented, at least one electoral-rich state with 10+ Electoral College votes has flipped in 44 of the last 46 cycles.

But just how often do states change their partisan vote in presidential elections?

Which states have seen the least movement every four years and which states have a rich history of switching their party preference?

Smart Politics examined the nearly 2,000 statewide votes for president across the last 46 elections since 1832 and found that the nation’s electoral maps are the most static they have been in history. Not only did the 2012 map record the lowest ever rate of statewide cycle-to-cycle change, but the country is also currently in the midst of its lowest rates of change in its electoral maps across the last three-, four-, five-, six-, seven-, eight-, and nine-cycle periods.

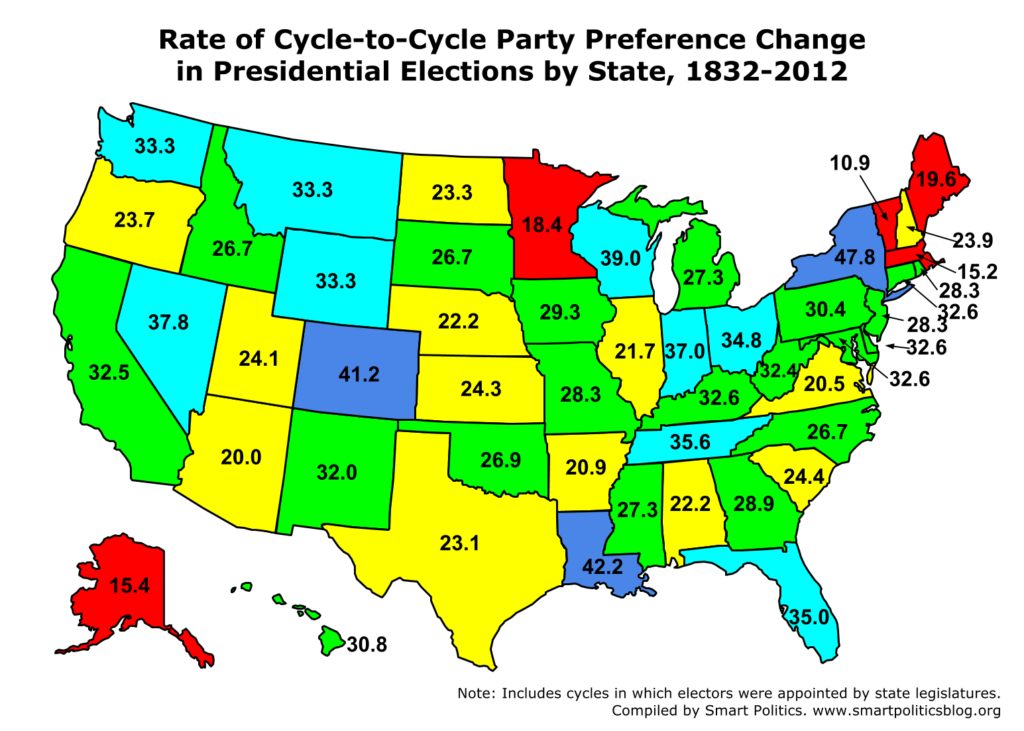

Since 1832, the first cycle after the birth of the modern two-party era in 1828, states have changed their partisan presidential preference 556 times out of 1,950 elections, or 28.5 percent of the time.

(Note: For the purposes of this report, states voting for nominees from the National Republican and the Whig Party (1832-1836) and from the Whig Party and the Republican Party (1852-1856) were not counted as partisan ‘flips.’ For Confederate states which did not vote in 1864 and/or 1868 as a result of the Civil War, the Election of 1860 was used as the reference data point for previous cycle comparisons).

The 2012 electoral map, however, saw only two states change from four years prior (four percent), with Mitt Romney picking off Indiana and North Carolina for the GOP.

This four percent change from 2008 to 2012 is the lowest since the first series of back-to-back elections in the two-party era (1828-1832).

Prior to 2012, the previous low water mark came in 1888, when two of 38 states flipped from the previous cycle (5.3 percent).

In that contest, Republican Benjamin Harrison narrowly picked up his home state of Indiana and Grover Cleveland’s delegate-rich home state of New York – both of which Cleveland had also won by very narrow margins in 1884.

Other cycles that saw particularly low rates of partisan flipping include 2004 at 6.0 percent (three of 50 states) with Iowa and New Mexico going to the Republicans (George W. Bush) and New Hampshire to the Democrats (John Kerry) and 1908 at 6.7 percent (three of 45 states) with Colorado, Nebraska, and Nevada moving to the Democratic column (William J. Bryan).

The 1924, 1936, 1944, and 1956 cycles all saw states flip at rates of 8.3 percent (four of 48 states each cycle).

The 2012 cycle was not an aberration, however, as presidential elections in the United States have seen a significant downturn in the cycle-to-cycle rate of partisan change compared to previous decades.

In fact, the country’s electoral maps have been changing at the lowest rate ever across three-cycle (9.3 percent), four-cycle (12.5 percent), five-cycle (12.0 percent), six-cycle (17.0 percent), seven-cycle (17.4 percent), eight-cycle (16.3 percent), and nine-cycle (18.2 percent) periods.

(Note: The 1884-1908 seven-cycle stretch also saw states flip at a 17.4 percent rate).

The election with the biggest cycle-to-cycle shift came with the Great Depression in 1932 when 34 states that backed Herbert Hoover in 1928 switched to Democrat Franklin Roosevelt (70.8 percent).

Close behind is the 1968 cycle when 35 states (70.0 percent) shifted after Lyndon Johnson’s landslide for the Democrats four years prior. Thirty states switched from Democratic to Republican, four switched from Republican to American Independent, and one switched from Democratic to American Independent.

Other cycles in which more than half the states flipped from the previous cycle were 1860 (61.3 percent, 19 of 31 states), 1912 (60.9 percent, 28 of 46 states), 1964 (60.0 percent, 30 of 50 states), and 1952 (56.3 percent, 27 of 48 states).

State-By-State Comparisons

Although the state has been reliably Democratic in recent years, New York has the most turbulent history when it comes to settling on its partisan support for presidential candidates.

The Empire State has changed its partisan vote for president in 22 of 46 cycles since 1832, or 47.8 percent of the time.

That includes a stretch of eight consecutive cycles from 1868 to 1896 in which the state did not cast its Electoral College votes for the same political party. After voting for Lincoln in 1864, New York voted for Democratic nominees in 1868, 1876, 1884, and 1892 and GOP nominees in 1872, 1880, 1888, and 1896.

Following New York is Louisiana which has changed its vote from the previous election in 19 of 45 cycles, or 42.2 percent.

The Pelican State owns the longest stretch of casting its votes for different political parties at nine cycles in a row from 1948 to 1980. During this stretch, Louisianans voted for State’s Rights nominee Strom Thurmond in 1948, Democrat Adlai Stevenson in 1952, Republican Dwight Eisenhower in 1956, Democrat Jack Kennedy in 1960, Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964, American Independent nominee George Wallace in 1968, Republican Richard Nixon in 1972, Democrat Jimmy Carter in 1976, and Republican Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Other long streaks of flip-flopping occurred in Indiana from 1876 to 1896 (six in a row), Alabama from 1964 to 1980 (six in a row), Maryland from 1852 to 1868 (five in a row), and New York from 1840 to 1856 (five in a row).

Three expected 2016 battleground states also have a fairly rich history of changing their partisan preference in presidential elections from cycle-to-cycle and round out the Top 5: Colorado at 41.2 percent (14 of 34 cycles), Wisconsin at 39.0 percent (16 of 41), and Nevada at 37.8 percent (14 of 37).

Both Colorado and Nevada have flipped in three out of the last six cycles, although Wisconsin is in the midst of its longest streak backing Democratic presidential nominees in state history at seven cycles in a row since 1988.

Completing the Top 10 are Indiana (37.0 percent), Tennessee (35.6 percent), Florida (35.0 percent), Ohio (34.8 percent), and Montana, Washington, and Wyoming (33.3 percent).

At the other end of the spectrum is Vermont, which has tallied the lowest rate of changing its vote for president over the decades, doing so in just one out of 10 elections since 1832.

Vermont’s appearance at the bottom of this list is not surprising considering the state also has the longest partisan presidential vote streak in the nation with its 27 consecutive cycles voting for Republican nominees from 1856 to 1960. (Note: That streak extends to 32 in a row if the Whigs are included).

The Green Mountain State has flipped its presidential vote just five times from the previous cycle out of the last 46 elections (10.9 percent): in 1832 (National Republican to Anti-Masonic), 1836 (Anti-Masonic to Whig), 1964 (Republican to Democrat), 1968 (Democrat to Republican), and 1992 (Republican to Democrat).

Four other states have flipped at a rate of less than one out of every five elections: Massachusetts (15.2 percent, seven of 46 cycles), Alaska (15.4 percent, two of 13), Minnesota (18.4 percent, seven of 38), and Maine (19.6 percent, nine of 46).

Minnesota’s low ranking is a product of a pair of long partisan streaks. The Gopher State voted Republican in its first 13 presidential elections through 1908 and in 2012 became the first state outside the South to vote for Democratic nominees in 10 consecutive contests (1976-2012).

Rounding out the Bottom 10 states are Arizona at #45 (20.0 percent), Virginia at #44 (20.5 percent), Arkansas at #43 (20.9 percent), Illinois at #42 (21.7 percent), and Alabama and Nebraska at #40 (22.2 percent).

Follow Smart Politics on Twitter.

1. Romney also managed to pick off the spot of light red in the plains known as “NE-02” (the above passage should read “…saw only two WHOLE states changed…”).

2. 2020: Regardless of its history, MI seems the one state most likely to change from the previous cycle, for its place in the R column seems no less flukish than IN (2008) and MT (1992) being in the D column for the presidential balloting. [FL, PA, NC, AZ, and WI also bear watching]