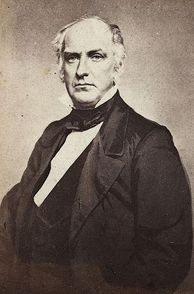

Edward Baker: The Lone Sitting Member of Congress Killed in War

The longtime friend of Abraham Lincoln died at the Battle of Balls Bluff with the rank of major general in 1861 while also serving in the U.S. Senate from Oregon

Born in London, England in 1811, Baker came to the United States at the age of four and grew up in Philadelphia.

As a young adult, Baker moved to Illinois to study law and was later elected to the State House where he served in 1837 along side a man who would later become his close friend, Abraham Lincoln.

Baker was later elected to the Illinois State Senate where he served from 1840 to 1844.

In 1844, Baker ran for Congress to Illinois’ 7th Congressional district and defeated Lincoln for the Whig Party nomination.

In the general election, Baker was victorious with 52.4 percent of the vote.

Representative Baker served in D.C. for a year and a half when, at the start of the Mexican-American War, he was commissioned as a colonel of the 4th Regiment of the Illinois Volunteer Infantry in July of 1846.

According to the U.S. Senate website:

“Representative Baker raised a regiment of troops and led them to the front. To boost congressional support for the unpopular war, he returned to the House Chamber in full uniform, lobbied his colleagues, resigned his seat, and rejoined his troops.”

Baker resigned from the U.S. House in December 1846 and ended up serving nearly 10 months in the military until May 1847.

According to the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, during the war Baker “participated in the siege of Vera Cruz and commanded a brigade at Cerro Gordo.”

After returning to Illinois, Baker was elected to a second term in Congress – this time to the state’s 6th Congressional District.

Baker won 50.9 percent of the vote in a three candidate race.

Baker served out the entire term but was not a candidate for renomination in 1850 and moved out west to continue his law practice.

In 1859, Baker ran for Congress as a Republican in California’s election for its two at-large seats, but finished fourth with 20.5 percent of the vote.

Closing out a full decade in California, Baker then moved to Oregon where he was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate in October 1860 to fill a vacant seat. He was the second individual to serve in the newly minted state’s Class II seat.

Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Colonel Baker raised the 71st Regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Later that summer Baker declined President Lincoln’s commission of brigadier general in order that he could continue to serve in the Senate.

(The Ineligibility Clause of the U.S. Constitution puts limitations, among other things, on the civil offices a sitting member of Congress may hold; Senator Baker serving as a brigadier general during the Civil War may have violated that Clause).

Baker was, however, appointed major general of the Volunteer Army early that fall.

On October 21, 1861, Baker was killed in Virginia in the Battle of Balls Bluff where the Union Army suffered significant casualties. According to the U.S. Senate website:

“Lightly schooled in military tactics, Baker gamely led his 1,700-member brigade across the Potomac River 40 miles north of the capital, up the steep ridge known as Ball’s Bluff, and into the range of waiting enemy guns. He died quickly–too soon to witness the stampede of his troops back over the 70-foot cliffs to the rock-studded river below. Nearly 1,000 were killed, wounded, or captured. This disaster led directly to the creation of the toughest congressional investigating committee in history–the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.”

Baker would be the first and only sitting U.S. Senator to be killed in battle in the Civil War – or any other war – due in part because the Department of War banned members of Congress from active duty service in World War II.

Follow Smart Politics on Twitter.